Wednesday, December 12, 2018

Kubernetes Federation Evolution

Authors: Irfan Ur Rehman (Huawei), Paul Morie (RedHat) and Shashidhara T D (Huawei)

Kubernetes provides great primitives for deploying applications to a cluster: it can be as simple as kubectl create -f app.yaml. Deploy apps across multiple clusters has never been that simple. How should app workloads be distributed? Should the app resources be replicated into all clusters, replicated into selected clusters, or partitioned into clusters? How is access to the clusters managed? What happens if some of the resources that a user wants to distribute pre-exist, in some or all of the clusters, in some form?

In SIG Multicluster, our journey has revealed that there are multiple possible models to solve these problems and there probably is no single best-fit, all-scenario solution. Federation, however, is the single biggest Kubernetes open source sub-project, and has seen the maximum interest and contribution from the community in this problem space. The project initially reused the Kubernetes API to do away with any added usage complexity for an existing Kubernetes user. This approach was not viable, because of the problems summarised below:

- Difficulties in re-implementing the Kubernetes API at the cluster level, as federation-specific extensions were stored in annotations.

- Limited flexibility in federated types, placement and reconciliation, due to 1:1 emulation of the Kubernetes API.

- No settled path to GA, and general confusion on API maturity; for example, Deployments are GA in Kubernetes but not even Beta in Federation v1.

The ideas have evolved further with a federation-specific API architecture and a community effort which now continues as Federation v2.

Conceptual Overview

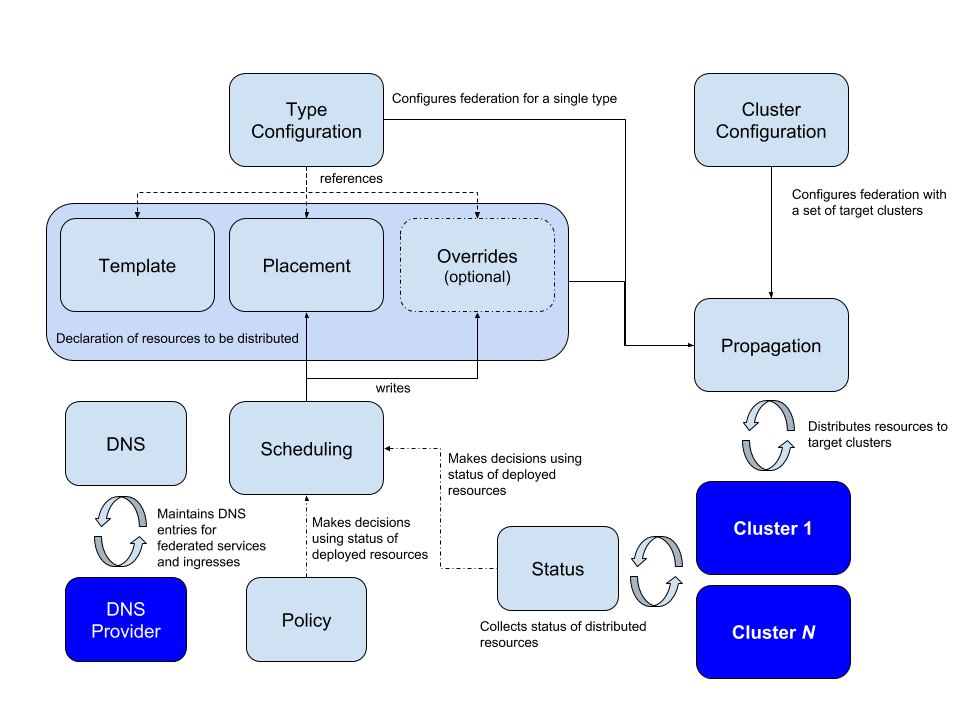

Because Federation attempts to address a complex set of problems, it pays to break the different parts of those problems down. Let’s take a look at the different high-level areas involved:

Kubernetes Federation v2 Concepts

Federating arbitrary resources

One of the main goals of Federation is to be able to define the APIs and API groups which encompass basic tenets needed to federate any given Kubernetes resource. This is crucial, due to the popularity of CustomResourceDefinitions as a way to extend Kubernetes with new APIs.

The workgroup arrived at a common definition of the federation API and API groups as ‘a mechanism that distributes “normal” Kubernetes API resources into different clusters’. The distribution in its most simple form could be imagined as simple propagation of this ‘normal Kubernetes API resource’ across the federated clusters. A thoughtful reader can certainly discern more complicated mechanisms, other than this simple propagation of the Kubernetes resources.

During the journey of defining building blocks of the federation APIs, one of the near term goals also evolved as ‘to be able to create a simple federation a.k.a. simple propagation of any Kubernetes resource or a CRD, writing almost zero code’. What ensued further was a core API group defining the building blocks as a Template resource, a Placement resource and an Override resource per given Kubernetes resource, a TypeConfig to specify sync or no sync for the given resource and associated controller(s) to carry out the sync. More details follow in the next section. Further sections will also talk about being able to follow a layered behaviour with higher-level federation APIs consuming the behaviour of these core building blocks, and users being able to consume whole or part of the API and associated controllers. Lastly, this architecture also allows the users to write additional controllers or replace the available reference controllers with their own, to carry out desired behaviour.

The ability to ‘easily federate arbitrary Kubernetes resources’, and a decoupled API, divided into building blocks APIs, higher level APIs and possible user intended types, presented such that different users can consume parts and write controllers composing solutions specific to them, makes a compelling case for Federation v2.

Federating resources: the details

Fundamentally, federation must be configured with two types of information:

- Which API types federation should handle

- Which clusters federation should target for distributing those resources.

For each API type that federation handles, different parts of the declared state live in different API resources:

- A

Templatetype holds the base specification of the resource - for example, a type calledFederatedReplicaSetholds the base specification of aReplicaSetthat should be distributed to the targeted clusters - A

Placementtype holds the specification of the clusters the resource should be distributed to - for example, a type calledFederatedReplicaSetPlacementholds information about which clustersFederatedReplicaSetsshould be distributed to - An optional

Overridestype holds the specification of how theTemplateresource should be varied in some clusters - for example, a type calledFederatedReplicaSetOverridesholds information about how aFederatedReplicaSetshould be varied in certain clusters.

These types are all associated by name - meaning that for a particular Template resource with name foo, the Placement and Override information for that resource are contained by the Override and Placement resources with the name foo and in the same namespace as the Template.

Higher-level behaviour

The architecture of the v2 API allows higher-level APIs to be constructed using the mechanics provided by the core API types (Template, Placement and Override), and associated controllers, for a given resource. In the community we uncovered a few use cases and implemented the higher-level APIs and associated controllers useful for those cases. Some of these types described in further sections also provide an useful reference to anybody interested in solving more complex use cases, building on top of the mechanics already available with the v2 API.

ReplicaSchedulingPreference

ReplicaSchedulingPreference provides an automated mechanism of distributing and maintaining total number of replicas for Deployment or ReplicaSet-based federated workloads into federated clusters. This is based on high-level user preferences given by the user. These preferences include the semantics of weighted distribution and limits (min and max) for distributing the replicas. These also include semantics to allow redistribution of replicas dynamically in case some replica Pods remain unscheduled in some clusters, for example due to insufficient resources in that cluster.

More details can be found at the user guide for ReplicaSchedulingPreferences.

Federated services & cross-cluster service discovery

Kubernetes Services are very useful in constructing a microservices architecture. There is a clear desire to deploy services across cluster, zone, region and cloud boundaries. Services that span clusters provide geographic distribution, enable hybrid and multi-cloud scenarios and improve the level of high availability beyond single cluster deployments. Customers who want their services to span one or more (possibly remote) clusters, need them to be reachable in a consistent manner from both within and outside their clusters.

Federated Service, at its core, contains a Template (a definition of a Kubernetes Service), a Placement (which clusters to be deployed into), an Override (optional variation in particular clusters) and a ServiceDNSRecord (specifying details on how to discover it).

Note: The federated service has to be of type LoadBalancer in order for it to be discoverable across clusters.

Discovering a federated service from Pods inside your federated clusters

By default, Kubernetes clusters come preconfigured with a cluster-local DNS server, as well as an intelligently constructed DNS search path, which together ensure that DNS queries like myservice, myservice.mynamespace, or some-other-service.other-namespace, issued by software running inside Pods, are automatically expanded and resolved correctly to the appropriate IP of Services running in the local cluster.

With the introduction of federated services and cross-cluster service discovery, this concept is extended to cover Kubernetes Services running in any other cluster across your cluster federation, globally. To take advantage of this extended range, you use a slightly different DNS name (e.g. myservice.mynamespace.myfederation) to resolve federated services. Using a different DNS name also avoids having your existing applications accidentally traversing cross-zone or cross-region networks and you incurring perhaps unwanted network charges or latency, without you explicitly opting in to this behavior.

Lets consider an example, using a service named nginx.

A Pod in a cluster in the us-central1-a availability zone needs to contact our nginx service. Rather than use the service’s traditional cluster-local DNS name (nginx.mynamespace, which is automatically expanded to nginx.mynamespace.svc.cluster.local) it can now use the service’s federated DNS name, which is nginx.mynamespace.myfederation. This will be automatically expanded and resolved to the closest healthy shard of my nginx service, wherever in the world that may be. If a healthy shard exists in the local cluster, that service’s cluster-local IP address will be returned (by the cluster-local DNS). This is exactly equivalent to non-federated service resolution.

If the Service does not exist in the local cluster (or it exists but has no healthy backend pods), the DNS query is automatically expanded to nginx.mynamespace.myfederation.svc.us-central1-a.us-central1.example.com. Behind the scenes, this finds the external IP of one of the shards closest to my availability zone. This expansion is performed automatically by the cluster-local DNS server, which returns the associated CNAME record. This results in a traversal of the hierarchy of DNS records, and ends up at one of the external IP’s of the federated service nearby.

It is also possible to target service shards in availability zones and regions other than the ones local to a Pod by specifying the appropriate DNS names explicitly, and not relying on automatic DNS expansion. For example, nginx.mynamespace.myfederation.svc.europe-west1.example.comwill resolve to all of the currently healthy service shards in Europe, even if the Pod issuing the lookup is located in the U.S., and irrespective of whether or not there are healthy shards of the service in the U.S. This is useful for remote monitoring and other similar applications.

Discovering a federated service from other clients outside your federated clusters

For external clients, automatic DNS expansion described is not currently possible. External clients need to specify one of the fully qualified DNS names of the federated service, be that a zonal, regional or global name. For convenience reasons, it is often a good idea to manually configure additional static CNAME records in your service, for example:

| SHORT NAME | CNAME |

|---|---|

| eu.nginx.acme.com | nginx.mynamespace.myfederation.svc.europe-west1.example.com |

| us.nginx.acme.com | nginx.mynamespace.myfederation.svc.us-central1.example.com |

| nginx.acme.com | nginx.mynamespace.myfederation.svc.example.com |

That way, your clients can always use the short form on the left, and always be automatically routed to the closest healthy shard on their home continent. All of the required failover is handled for you automatically by Kubernetes cluster federation.

As further reading, a more elaborate example for users is available in the Multi-Cluster Service DNS with ExternalDNS guide.

Try it yourself

To get started with Federation v2, please refer to the user guide. Deployment can be accomplished with a Helm chart, and once the control plane is available, the user guide’s example can be used to get some hands-on experience with using Federation V2.

Federation v2 can be deployed in both cluster-scoped and namespace-scoped configurations. A cluster-scoped deployment will require cluster-admin privileges to both host and member clusters, and may be a good fit for evaluating federation on clusters that are not running critical workloads. Namespace-scoped deployment requires access to only a single namespace on host and member clusters, and is a better fit for evaluating federation on clusters running workloads. Most of the user guide refers to cluster-scoped deployment, with the namespaced federation section documenting how use of a namespaced deployment differs. The same cluster can host multiple federations, and clusters can be part of multiple federations when using namespaced federation.

Next Steps

As we noted in the beginning of this post, the multicluster problem space is extremely broad. It can be difficult to know exactly how to handle such broad problem spaces without concrete pieces of software to frame those conversations around. Our hope in the Federation working group is that Federation v2 can be a concrete artifact to frame discussions around. We would love to know experiences that folks have had in this problem space, how they feel about Federation v2, and what use-cases they’re interested in exploring in the future.

Please feel welcome to join us at the sig-multicluster slack channel or at Federation working group meetings on Wednesdays at 07:30 PST.