Friday, August 03, 2018

Out of the Clouds onto the Ground: How to Make Kubernetes Production Grade Anywhere

Authors: Steven Wong (VMware), Michael Gasch (VMware)

This blog offers some guidelines for running a production grade Kubernetes cluster in an environment like an on-premise data center or edge location.

What does it mean to be “production grade”?

- The installation is secure

- The deployment is managed with a repeatable and recorded process

- Performance is predictable and consistent

- Updates and configuration changes can be safely applied

- Logging and monitoring is in place to detect and diagnose failures and resource shortages

- Service is “highly available enough” considering available resources, including constraints on money, physical space, power, etc.

- A recovery process is available, documented, and tested for use in the event of failures

In short, production grade means anticipating accidents and preparing for recovery with minimal pain and delay.

This article is directed at on-premise Kubernetes deployments on a hypervisor or bare-metal platform, facing finite backing resources compared to the expansibility of the major public clouds. However, some of these recommendations may also be useful in a public cloud if budget constraints limit the resources you choose to consume.

A single node bare-metal Minikube deployment may be cheap and easy, but is not production grade. Conversely, you’re not likely to achieve Google’s Borg experience in a retail store, branch office, or edge location, nor are you likely to need it.

This blog offers some guidance on achieving a production worthy Kubernetes deployment, even when dealing with some resource constraints.

Critical components in a Kubernetes cluster

Before we dive into the details, it is critical to understand the overall Kubernetes architecture.

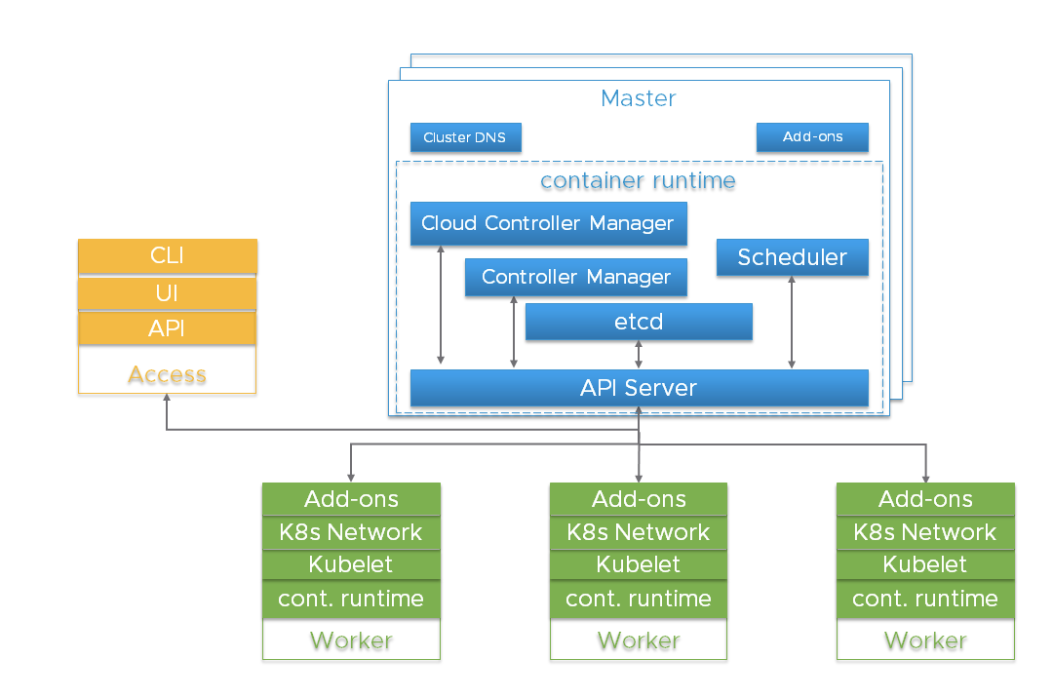

A Kubernetes cluster is a highly distributed system based on a control plane and clustered worker node architecture as depicted below.

Typically the API server, Controller Manager and Scheduler components are co-located within multiple instances of control plane (aka Master) nodes. Master nodes usually include etcd too, although there are high availability and large cluster scenarios that call for running etcd on independent hosts. The components can be run as containers, and optionally be supervised by Kubernetes, i.e. running as statics pods.

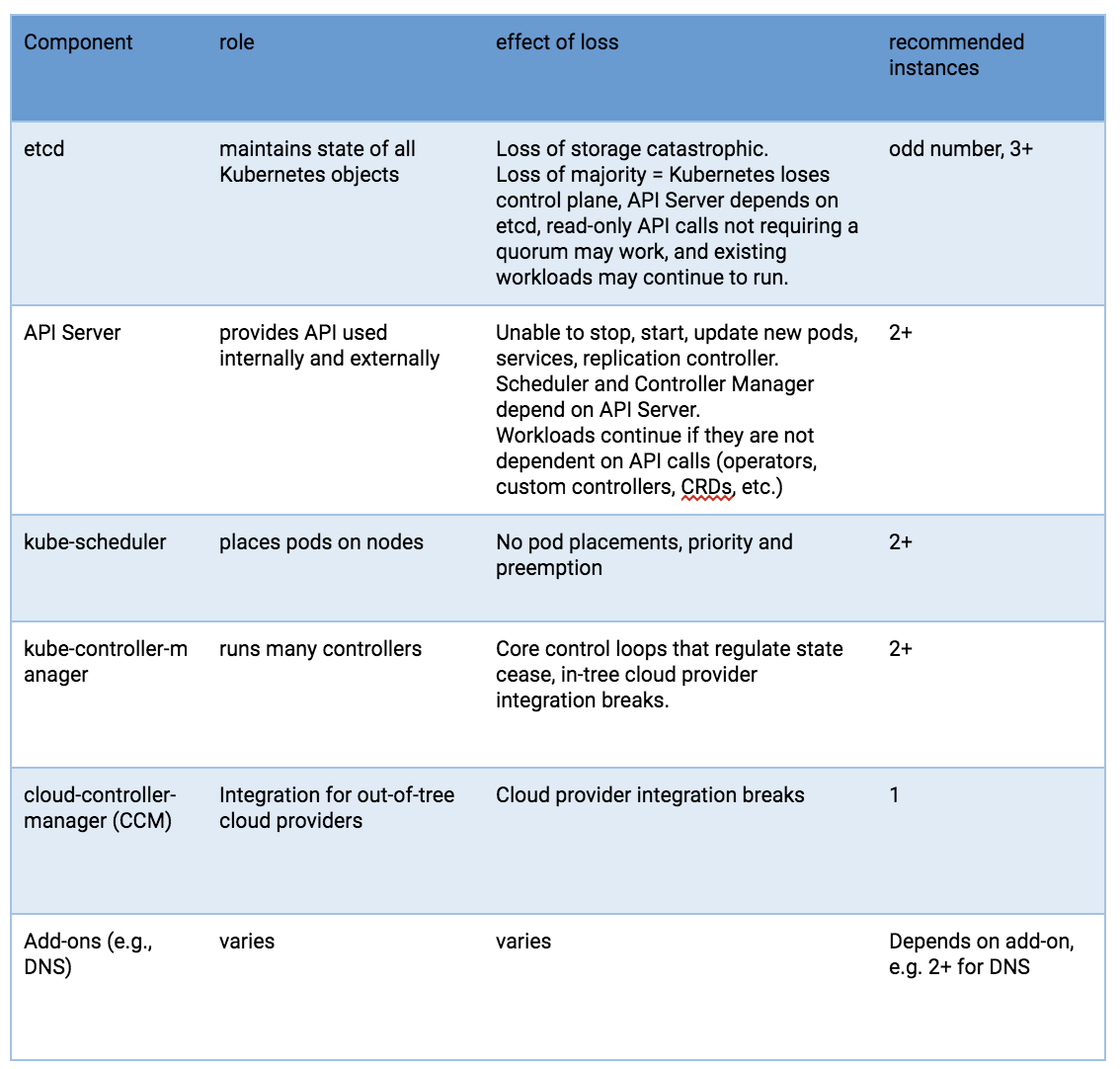

For high availability, redundant instances of these components are used. The importance and required degree of redundancy varies.

Kubernetes components from an HA perspective

Risks to these components include hardware failures, software bugs, bad updates, human errors, network outages, and overloaded systems resulting in resource exhaustion. Redundancy can mitigate the impact of many of these hazards. In addition, the resource scheduling and high availability features of a hypervisor platform can be useful to surpass what can be achieved using the Linux operating system, Kubernetes, and a container runtime alone.

The API Server uses multiple instances behind a load balancer to achieve scale and availability. The load balancer is a critical component for purposes of high availability. Multiple DNS API Server ‘A’ records might be an alternative if you don’t have a load balancer.

The kube-scheduler and kube-controller-manager engage in a leader election process, rather than utilizing a load balancer. Since a cloud-controller-manager is used for selected types of hosting infrastructure, and these have implementation variations, they will not be discussed, beyond indicating that they are a control plane component.

Pods running on Kubernetes worker nodes are managed by the kubelet agent. Each worker instance runs the kubelet agent and a CRI-compatible container runtime. Kubernetes itself is designed to monitor and recover from worker node outages. But for critical workloads, hypervisor resource management, workload isolation and availability features can be used to enhance availability and make performance more predictable.

etcd

etcd is the persistent store for all Kubernetes objects. The availability and recoverability of the etcd cluster should be the first consideration in a production-grade Kubernetes deployment.

A five-node etcd cluster is a best practice if you can afford it. Why? Because you could engage in maintenance on one and still tolerate a failure. A three-node cluster is the minimum recommendation for production-grade service, even if only a single hypervisor host is available. More than seven nodes is not recommended except for very large installations straddling multiple availability zones.

The minimum recommendation for hosting an etcd cluster node is 2GB of RAM with 8GB of SSD-backed disk. Usually, 8GB RAM and a 20GB disk will be enough. Disk performance affects failed node recovery time. See https://coreos.com/etcd/docs/latest/op-guide/hardware.html for more on this.

Consider multiple etcd clusters in special situations

For very large Kubernetes clusters, consider using a separate etcd cluster for Kubernetes events so that event storms do not impact the main Kubernetes API service. If you use flannel networking, it retains configuration in etcd and may have differing version requirements than Kubernetes, which can complicate etcd backup – consider using a dedicated etcd cluster for flannel.

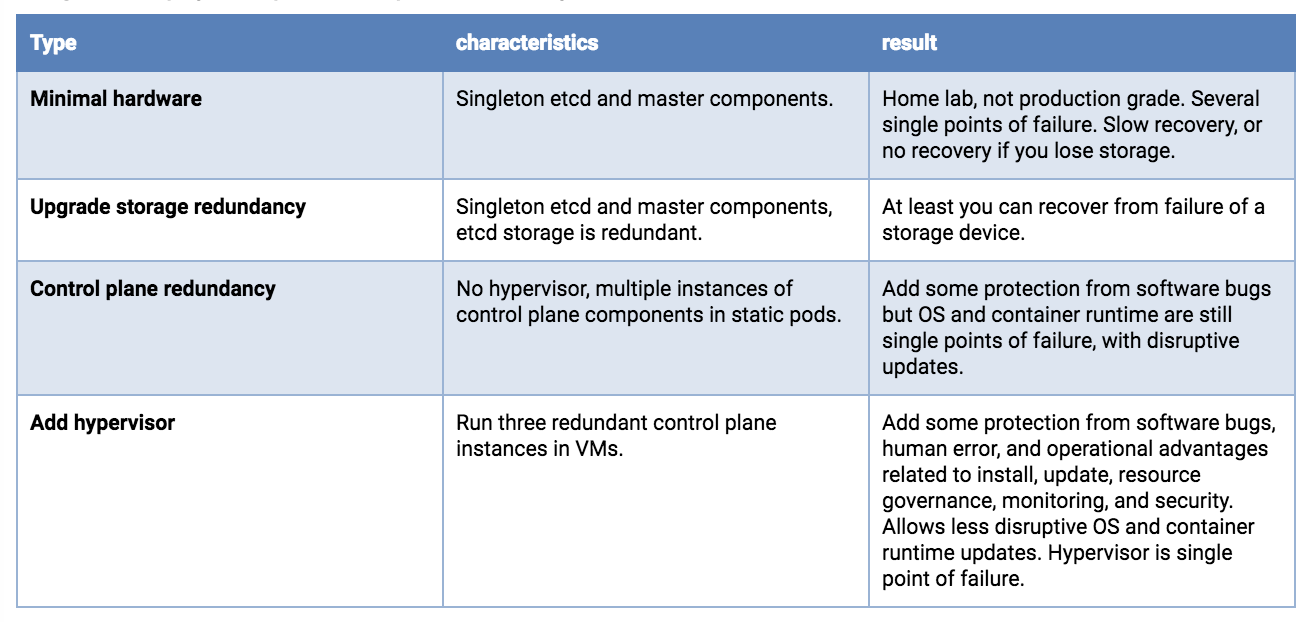

Single host deployments

The availability risk list includes hardware, software and people. If you are limited to a single host, the use of redundant storage, error-correcting memory and dual power supplies can reduce hardware failure exposure. Running a hypervisor on the physical host will allow operation of redundant software components and add operational advantages related to deployment, upgrade, and resource consumption governance, with predictable and repeatable performance under stress. For example, even if you can only afford to run singletons of the master services, they need to be protected from overload and resource exhaustion while competing with your application workload. A hypervisor can be more effective and easier to manage than configuring Linux scheduler priorities, cgroups, Kubernetes flags, etc.

If resources on the host permit, you can deploy three etcd VMs. Each of the etcd VMs should be backed by a different physical storage device, or they should use separate partitions of a backing store using redundancy (mirroring, RAID, etc).

Dual redundant instances of the API server, scheduler and controller manager would be the next upgrade, if your single host has the resources.

Single host deployment options, least production worthy to better

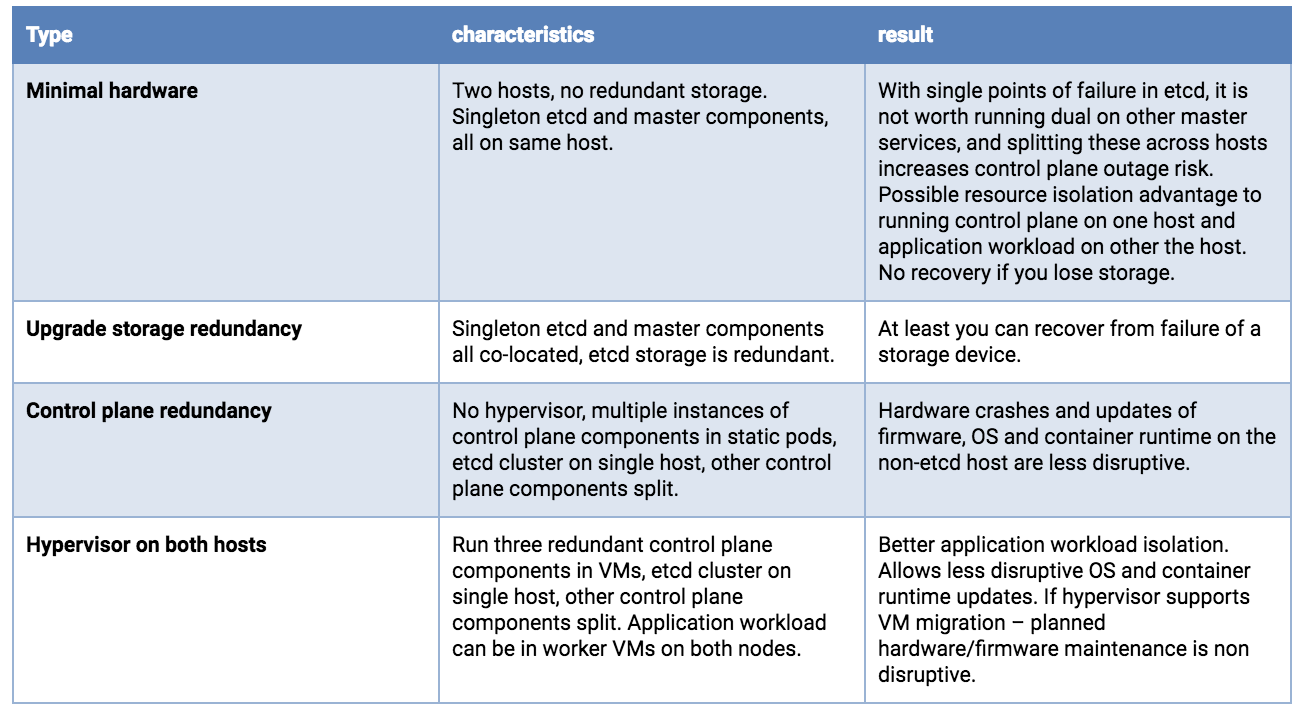

Dual host deployments

With two hosts, storage concerns for etcd are the same as a single host, you want redundancy. And you would preferably run 3 etcd instances. Although possibly counter-intuitive, it is better to concentrate all etcd nodes on a single host. You do not gain reliability by doing a 2+1 split across two hosts - because loss of the node holding the majority of etcd instances results in an outage, whether that majority is 2 or 3. If the hosts are not identical, put the whole etcd cluster on the most reliable host.

Running redundant API Servers, kube-schedulers, and kube-controller-managers is recommended. These should be split across hosts to minimize risk due to container runtime, OS and hardware failures.

Running a hypervisor layer on the physical hosts will allow operation of redundant software components with resource consumption governance, and can have planned maintenance operational advantages.

Dual host deployment options, least production worthy to better

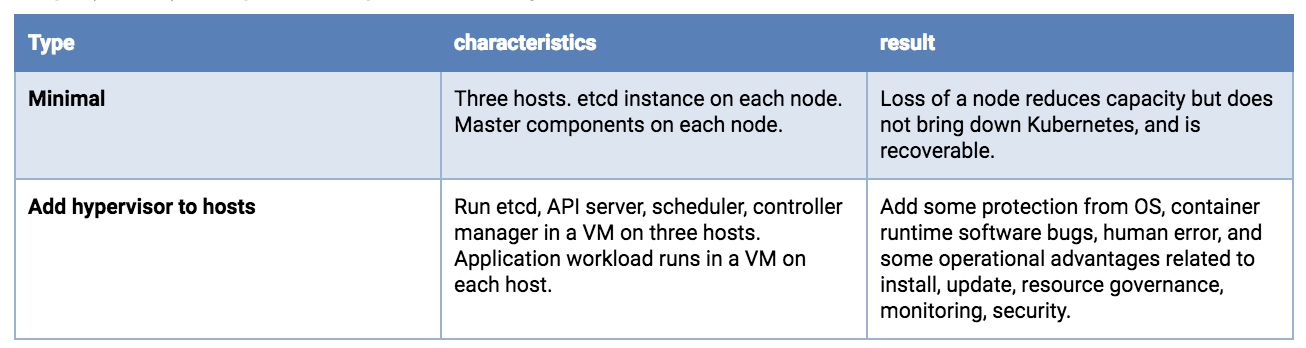

Triple (or larger) host deployments – Moving into uncompromised production-grade service Splitting etcd across three hosts is recommended. A single hardware failure will reduce application workload capacity, but should not result in a complete service outage.

With very large clusters, more etcd instances will be required.

Running a hypervisor layer offers operational advantages and better workload isolation. It is beyond the scope of this article, but at the three-or-more host level, advanced features may be available (clustered redundant shared storage, resource governance with dynamic load balancing, automated health monitoring with live migration or failover).

Triple (or more) host options, least production worthy to better

Kubernetes configuration settings

Master and Worker nodes should be protected from overload and resource exhaustion. Hypervisor features can be used to isolate critical components and reserve resources. There are also Kubernetes configuration settings that can throttle things like API call rates and pods per node. Some install suites and commercial distributions take care of this, but if you are performing a custom Kubernetes deployment, you may find that the defaults are not appropriate, particularly if your resources are small or your cluster is large.

Resource consumption by the control plane will correlate with the number of pods and the pod churn rate. Very large and very small clusters will benefit from non-default settings of kube-apiserver request throttling and memory. Having these too high can lead to request limit exceeded and out of memory errors.

On worker nodes, Node Allocatable should be configured based on a reasonable supportable workload density at each node. Namespaces can be created to subdivide the worker node cluster into multiple virtual clusters with resource CPU and memory quotas. Kubelet handling of out of resource conditions can be configured.

Security

Every Kubernetes cluster has a cluster root Certificate Authority (CA). The Controller Manager, API Server, Scheduler, kubelet client, kube-proxy and administrator certificates need to be generated and installed. If you use an install tool or a distribution this may be handled for you. A manual process is described here. You should be prepared to reinstall certificates in the event of node replacements or expansions.

As Kubernetes is entirely API driven, controlling and limiting who can access the cluster and what actions they are allowed to perform is essential. Encryption and authentication options are addressed in this documentation.

Kubernetes application workloads are based on container images. You want the source and content of these images to be trustworthy. This will almost always mean that you will host a local container image repository. Pulling images from the public Internet can present both reliability and security issues. You should choose a repository that supports image signing, security scanning, access controls on pushing and pulling images, and logging of activity.

Processes must be in place to support applying updates for host firmware, hypervisor, OS, Kubernetes, and other dependencies. Version monitoring should be in place to support audits.

Recommendations:

- Tighten security settings on the control plane components beyond defaults (e.g., locking down worker nodes)

- Utilize Pod Security Policies

- Consider the NetworkPolicy integration available with your networking solution, including how you will accomplish tracing, monitoring and troubleshooting.

- Use RBAC to drive authorization decisions and enforcement.

- Consider physical security, especially when deploying to edge or remote office locations that may be unattended. Include storage encryption to limit exposure from stolen devices and protection from attachment of malicious devices like USB keys.

- Protect Kubernetes plain-text cloud provider credentials (access keys, tokens, passwords, etc.)

Kubernetes secret objects are appropriate for holding small amounts of sensitive data. These are retained within etcd. These can be readily used to hold credentials for the Kubernetes API but there are times when a workload or an extension of the cluster itself needs a more full-featured solution. The HashiCorp Vault project is a popular solution if you need more than the built-in secret objects can provide.

Disaster Recovery and Backup

Utilizing redundancy through the use of multiple hosts and VMs helps reduce some classes of outages, but scenarios such as a sitewide natural disaster, a bad update, getting hacked, software bugs, or human error could still result in an outage.

A critical part of a production deployment is anticipating a possible future recovery.

It’s also worth noting that some of your investments in designing, documenting, and automating a recovery process might also be re-usable if you need to do large-scale replicated deployments at multiple sites.

Elements of a DR plan include backups (and possibly replicas), replacements, a planned process, people who can carry out the process, and recurring training. Regular test exercises and chaos engineering principles can be used to audit your readiness.

Your availability requirements might demand that you retain local copies of the OS, Kubernetes components, and container images to allow recovery even during an Internet outage. The ability to deploy replacement hosts and nodes in an “air-gapped” scenario can also offer security and speed of deployment advantages.

All Kubernetes objects are stored on etcd. Periodically backing up the etcd cluster data is important to recover Kubernetes clusters under disaster scenarios, such as losing all master nodes.

Backing up an etcd cluster can be accomplished with etcd’s built-in snapshot mechanism, and copying the resulting file to storage in a different failure domain. The snapshot file contains all the Kubernetes states and critical information. In order to keep the sensitive Kubernetes data safe, encrypt the snapshot files.

Using disk volume based snapshot recovery of etcd can have issues; see #40027. API-based backup solutions (e.g., Ark) can offer more granular recovery than a etcd snapshot, but also can be slower. You could utilize both snapshot and API-based backups, but you should do one form of etcd backup as a minimum.

Be aware that some Kubernetes extensions may maintain state in independent etcd clusters, on persistent volumes, or through other mechanisms. If this state is critical, it should have a backup and recovery plan.

Some critical state is held outside etcd. Certificates, container images, and other configuration- and operation-related state may be managed by your automated install/update tooling. Even if these items can be regenerated, backup or replication might allow for faster recovery after a failure. Consider backups with a recovery plan for these items:

- Certificate and key pairs

- CA

- API Server

- Apiserver-kubelet-client

- ServiceAccount signing

- “Front proxy”

- Front proxy client

- Critical DNS records

- IP/subnet assignments and reservations

- External load-balancers

- kubeconfig files

- LDAP or other authentication details

- Cloud provider specific account and configuration data

Considerations for your production workloads

Anti-affinity specifications can be used to split clustered services across backing hosts, but at this time the settings are used only when the pod is scheduled. This means that Kubernetes can restart a failed node of your clustered application, but does not have a native mechanism to rebalance after a fail back. This is a topic worthy of a separate blog, but supplemental logic might be useful to achieve optimal workload placements after host or worker node recoveries or expansions. The Pod Priority and Preemption feature can be used to specify a preferred triage in the event of resource shortages caused by failures or bursting workloads.

For stateful services, external attached volume mounts are the standard Kubernetes recommendation for a non-clustered service (e.g., a typical SQL database). At this time Kubernetes managed snapshots of these external volumes is in the category of a roadmap feature request, likely to align with the Container Storage Interface (CSI) integration. Thus performing backups of such a service would involve application specific, in-pod activity that is beyond the scope of this document. While awaiting better Kubernetes support for a snapshot and backup workflow, running your database service in a VM rather than a container, and exposing it to your Kubernetes workload may be worth considering.

Cluster-distributed stateful services (e.g., Cassandra) can benefit from splitting across hosts, using local persistent volumes if resources allow. This would require deploying multiple Kubernetes worker nodes (could be VMs on hypervisor hosts) to preserve a quorum under single point failures.

Other considerations

Logs and metrics (if collected and persistently retained) are valuable to diagnose outages, but given the variety of technologies available it will not be addressed in this blog. If Internet connectivity is available, it may be desirable to retain logs and metrics externally at a central location.

Your production deployment should utilize an automated installation, configuration and update tool (e.g., Ansible, BOSH, Chef, Juju, kubeadm, Puppet, etc.). A manual process will have repeatability issues, be labor intensive, error prone, and difficult to scale. Certified distributions are likely to include a facility for retaining configuration settings across updates, but if you implement your own install and config toolchain, then retention, backup and recovery of the configuration artifacts is essential. Consider keeping your deployment components and settings under a version control system such as Git.

Outage recovery

Runbooks documenting recovery procedures should be tested and retained offline – perhaps even printed. When an on-call staff member is called up at 2 am on a Friday night, it may not be a great time to improvise. Better to execute from a pre-planned, tested checklist – with shared access by remote and onsite personnel.

Final thoughts

Buying a ticket on a commercial airline is convenient and safe. But when you travel to a remote location with a short runway, that commercial Airbus A320 flight isn’t an option. This doesn’t mean that air travel is off the table. It does mean that some compromises are necessary.

The adage in aviation is that on a single engine aircraft, an engine failure means you crash. With twin engines, at the very least, you get more choices of where you crash. Kubernetes on a small number of hosts is similar, and if your business case justifies it, you might scale up to a larger fleet of mixed large and small vehicles (e.g., FedEx, Amazon).

Those designing a production-grade Kubernetes solution have a lot of options and decisions. A blog-length article can’t provide all the answers, and can’t know your specific priorities. We do hope this offers a checklist of things to consider, along with some useful guidance. Some options were left “on the cutting room floor” (e.g., running Kubernetes components using self-hosting instead of static pods). These might be covered in a follow up if there is interest. Also, Kubernetes’ high enhancement rate means that if your search engine found this article after 2019, some content might be past the “sell by” date.